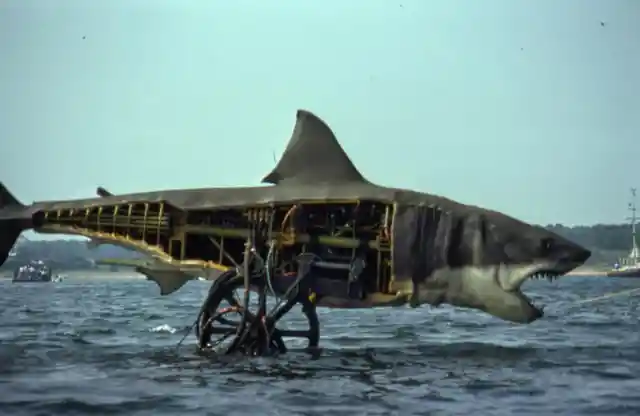

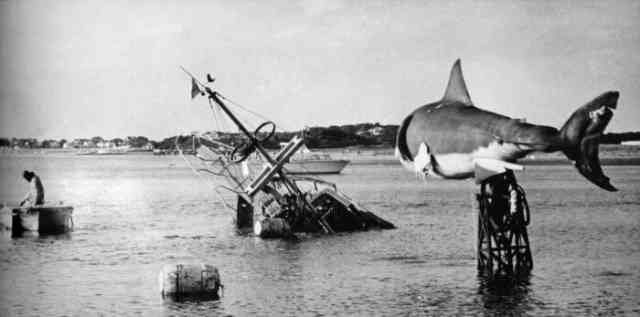

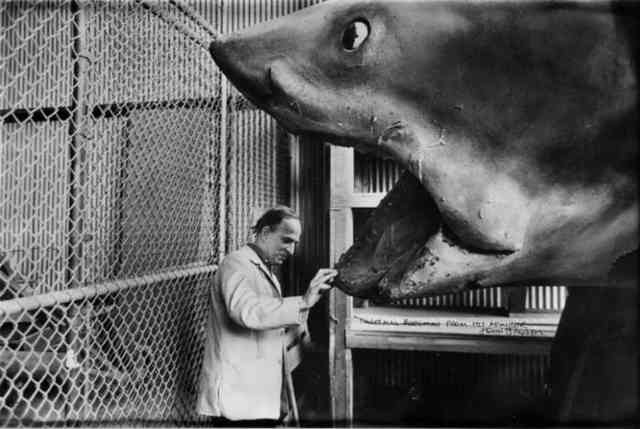

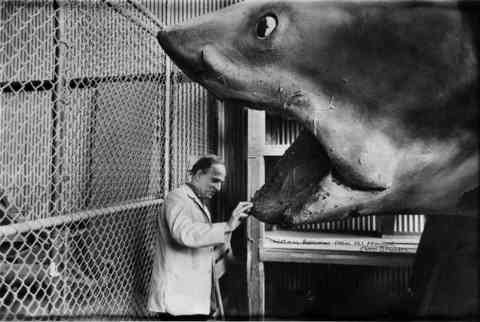

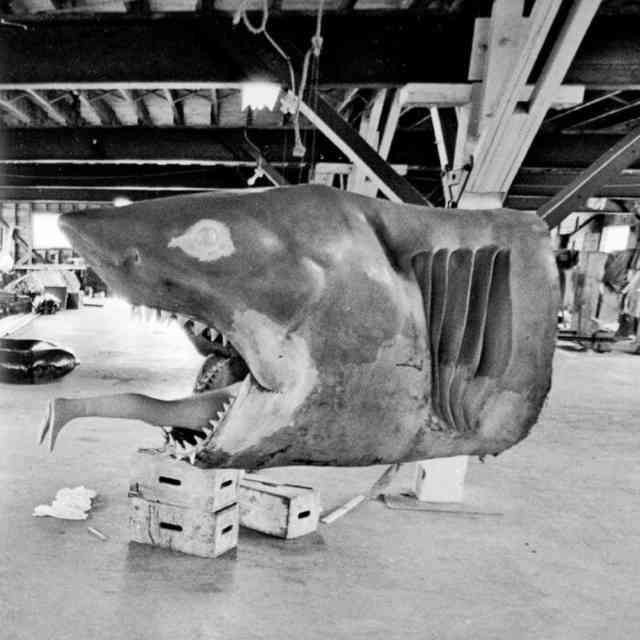

Not one, but three mechanical sharks were constructed for the film.

One of the most beloved movies of all time, one of Steven Spielberg's earliest masterpieces, and the 7th highest grossing movie of all time, Jaws has left a major mark on the entertainment industry. Not only have it’s then-cutting-edge use of effects, it’s terror-inducing writing, and game changing cinematography left a lasting impression on audiences around the world, the production was wrought with complications and secrets never before revealed… until now.

Let’s take a look at 40 facts and secrets from the set of Steven Spielberg's Jaws!

Knowing about the issue with captive sharks, the film crew decided to create a mechanical one instead.

The sharks were collectively named “Bruce.”

Three sharks were ultimately constructed: a “left” and “right” shark for side shots, and a full sized shark for all other shots.

Named after Steven Spielberg’s lawyer “Bruce M. Ramer”, the shark has since been a running joke with the two.

The sharks… barely worked.

Known as one of the nicest guys in Hollywood, they always found it funny that he got turned into one of the most iconic movie monsters of the 20th century.

The Sharks were connected to a 16-ton platform on the ocean floor.

After the full-sized shark sank during its first time in the water, the crew also nicknamed the shark “Flaws” or the “Great White Turd.” The sharks have now been known as one of the biggest failures in special effects… but the majority of the public would never know.

Nicknamed the “Iron Monster”, the sharks were connected to giant mechanical arm used to control the sharks.

The sharks were a major disappointment

The Arm was then attached to a 16-ton platform on the ocean floor.

With the combined cost of $225,000 (nearly $1 Million in today’s currency), the sharks were a huge letdown for the crew.

The first shark doesn’t appear until 1 hour and 21 minutes into the film.

Due to the fact that the sharks just didn’t work, the movie was “reorganized”.

Due to the malfunctioning sharks, the movie was “reorganized” to buy the production more time to figure out the shark issue.

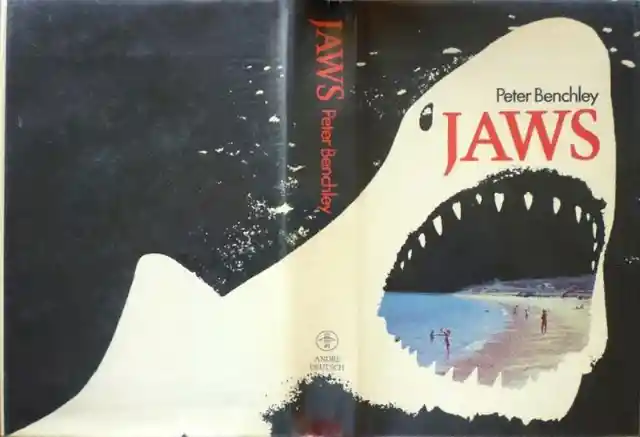

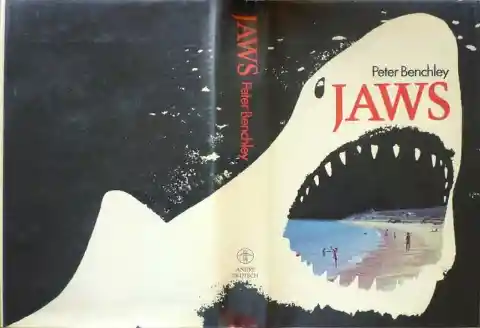

The movie Jaws was developed from a book

In the end, Jaws only had 4 minutes of screen time.

Benchley later regretted writing Jaws.

Jaws was written by Peter Benchley, and though he says the book is pure fiction, Benchley says he was inspired by the capture of a 4,500-pound shark off the coast of Montauk in 1964.

Benchley, who has since become an ocean conservationist, said he regretted writing a book that portrayed sharks in such a cold-blooded manner.

The book was originally called Silence of the Deep

He feels responsible for the bad wrap that sharks get in pop-culture these days.

Benchley originally titled the book Silence in the Deep before he asked his father, the children’s books author Nathaniel Benchley, for suggestions. The senior Benchley sent back a list of 200 possible titles, including the now-famous monosyllabic title, and some lengthier options; for example, Wha’s That Noshin’ On My Laig?

Steven Spielberg originally thought that the movie was about a dentist.

The title Jaws was the only one both Peter Benchley and his editors could agree upon.

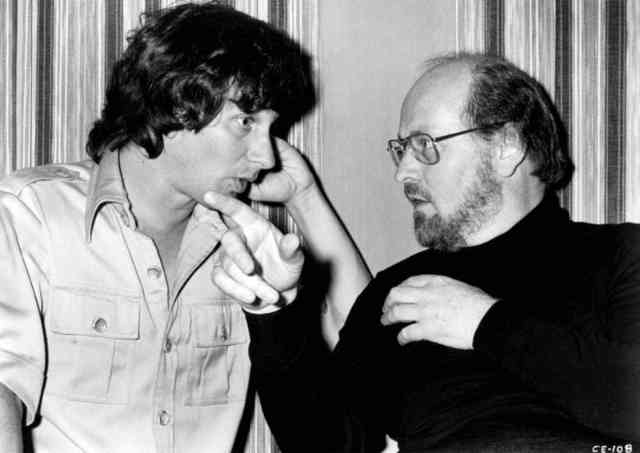

Steven Spielberg, the film’s director, first became aware of the book when he noticed it on top of a large stack of papers in his producer’s office.

Jaws is technically the first “Summer Blockbuster.”

He initially thought it was about a dentist.

Jaws was set to be released over the Christmas season, but Spielberg took so long filming that the movie had a summer release date, which was traditionally reserved for low-end movies.

Angry locals left a dead brown shark on the porch of the Martha’s Vineyard production office.

The filming delay is what spurred Jaws to become the first movie to define the concept of a “summer blockbuster.”

The original filming took place off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard during May and June, but Spielberg had to extend the filming by three months because of shooting complications.

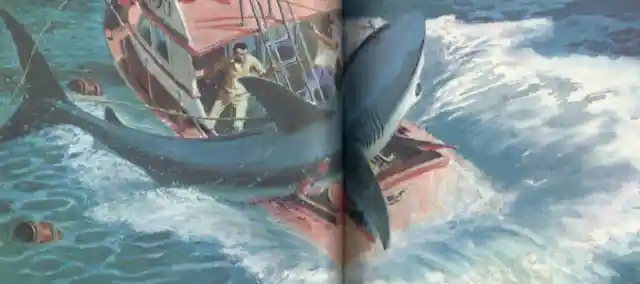

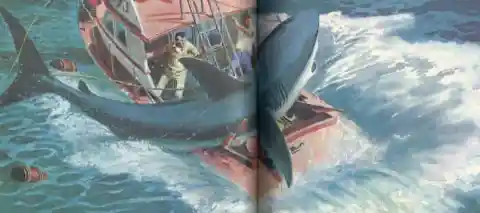

A real shark incident made it into the film.

A local prankster, apparently angered by the outsiders overstaying their welcome, left a dead brown shark on the porch of the production office.

A real shark (not a great white) used in filming got tangled in rope and smashed the underwater cage, which contained a real actor for scale. Spielberg liked this footage so much, he decided to change the script and have Hooper, the out-of-town oceanographer, escape during this attack.

Steven Spielberg wasn’t the original director.

None of it was planned.

The first director, Dick Richards, was fired after a production meeting in which he continually referred to the shark as a whale.

The first director, Dick Richards, was fired after a production meeting in which he continually referred to the shark as a whale.

Spielberg didn’t want to direct the movie out of fear of being typecast.

John Sturges to was actually set to direct the film, before the studio considered Dick Richards.

Three months before production was set to begin, Spielberg decided he wanted to direct a different movie (he didn’t want to be typecast as a “truck and shark” director). He went to speak with the producers, who knew he wanted to back out.

Producers were forbidden from using a real shark in the film.

When Spielberg saw that they had worn Jaws crew t-shirts, all three started laughing, and Spielberg said, “Never mind.” Also, Spielberg was under contract with the studio and they wouldn’t let him back down.

Producers knew they couldn’t use a real great white shark in the movie because this breed died quickly in captivity; at the time, the current record for keeping a one alive in confinement was 11 days.

Spielberg turned to Hitchcock for his sense of dread.

Scientists believe that great whites died from depression and self-starvation due to the stress of capture.

Curious mariners ruined countless shots.

In lieu of more face time with sharks, Spielberg says he channeled Alfred Hitchcock to let an invisible threat terrorize the audience.

The odd-looking mechanized sharks attracted fellow mariners, who would often ruin a shot by steering over to ask what the production crew was doing.

The crew lost 10 days of filming because of the New York Yacht Club’s Annual Cruise.

It would take up to six hours to set up shots again, and with a budget of that caliber, reshoots would sometimes cost up to 10s of thousands of dollars per take.

The crew also lost 10 days of filming during the summer boating season. The first issue was the New York Yacht Club’s Annual Cruise; boat after boat passed by on the supposed-to-be-empty horizon.

The film’s initial budget was very bare bones.

This was followed by another parade of boats en route to the America’s Cup race in Newport, Rhode Island.

The film’s initial budget was $3.5 million, but it wound up costing around $8 million to make, the equivalent of $35 million in today’s dollars.

The crew was forbidden to build any physical set in Martha’s Vineyard.

(Compare that with Pirates of the Caribbean’s $341.8 million budget or Titanic’s $294.3 million cost).

The production crew wasn’t allowed to build sets for movie scenes on Martha’s Vineyard, save for the set of Quint’s boathouse. Town officials only gave their consent because the crew agreed to build on an abandoned lot, tear down after, and replace everything that had been there—including the pre-existing trash on the ground.

The actor’s used in scenes with actual sharks were cast for their short stature

Spielberg didn’t originally like the theme-song.

The sharks used in the film were smaller than Spielberg wanted, so he hired a short actor specifically for those scenes.

The first time he heard John William’s opening track, he laughed at its simplicity.

John Williams actually played the music for the high school band scene.

He later conceded that the music made the movie more thrilling.

In an early scene, a high school band is playing a Sousa march. The music was actually recorded by John Williams and his band, but according to Williams, many of the talented musicians found it difficult to play so poorly.

Charlton Heston was supposed to be Police Chief Martin Brody.

Spielberg played the clarinet for the recording, which Williams said, “added just the right amateur quality to the piece.”

Charlton Heston was considered for the role of Police Chief Martin Brody, but Spielberg decided to go with a less-known actor because he didn’t want the audience to immediately identify Brody as the heroic savior (based on Heston’s previous film roles).

Charlton Heston was considered for the role of Police Chief Martin Brody, but Spielberg decided to go with a less-known actor because he didn’t want the audience to immediately identify Brody as the heroic savior (based on Heston’s previous film roles).

Roy Scheider was cast as the lead by coincidence.

Heston reportedly refused to ever work with the director.

Roy Scheider, the actor who did get the leading role, happened upon it by coincidence.

Scheider improvised many lines in the film.

At a party, he heard Spielberg describing the scene where the shark leaps up onto the boat, and immediately asked for a role in the film.

The production company Bad Hat Harry was actually named after a line from the movie.

One of the movies famous lines “You’re going to need a bigger boat” was actually improvised.

Bad Hat Harry, the production company behind such movies as the X-Men franchise and Superman Returns, actually was inspired by a scene in Jaws.

Bad Hat Harry, the production company behind such movies as the X-Men franchise and Superman Returns, actually was inspired by a scene in Jaws.

Jaws author Peter Benchley makes a cameo in the film.

Chief Brody tells a beachgoer that he has an ugly swimming cap: “That’s some bad hat, Harry!”

Appearing in the film as a newspaper reporter, the cameo is a homage to his prior occupation.

The terrified beachgoers were actually the townspeople of Martha’s Vineyard.

Before penning Jaws, Peter was a writer at the Washington Post.

Paid $64 per day, the citizens of Martha’s Vineyard were employed as extras in the film. Their motive?

The water during the 4th of July scene was a brisk 64 degrees.

To run across the beach in despair of the impending shark attack.

Cameraman Bill Butler invented the revolutionary “Water Box”.

Due to the water’s less-than-ideal temperature, the beachgoing extras had more than a little motivation to leave the water as soon as possible.

Steven Spielberg wanted the audience to feel like they were drowning in the ocean, so cameraman invented the Water Box: A box made out of panes of glass that the camera sat in.

The film originally had an R rating.

This allowed for the camera to be submerged underwater to get a never-before-seen effect in cinema.

Due to a graphic scene involving the severing of a leg, the film was initially given an R rating.

Artist Roger Kastel designed the films iconic poster.

Once the scene was removed, the films rating dropped down to PG (PG-13 was nonexistent at the time.)

The mechanical sharks were destroyed after filming.

The swimmer in the poster was a model he was sketching for an ad in Good Housekeeping; he asked her to stay a little longer and lie on a stool in a swimming position.

After the hardship that the mechanical sharks brought the studio and the crew, everyone was happy to see them gone. But one important piece of the film survived: The Orca, the films famous boat.

After the hardship that the mechanical sharks brought the studio and the crew, everyone was happy to see them gone. But one important piece of the film survived: The Orca, the films famous boat.

The Orca was unfortunately scrapped a few years later.

Ending up at Universal Studios Hollywood, Spielberg would often visit the park to visit the boat and reminisce about the movie that launched his career.

One day in 1996 when Spielberg went to visit the Orca, he discovered it had disappeared. According to Spielberg, a Universal Studios employee had decided to chop up the mildewed and termite-infested boat.

The movie originally ended with the shark dying from blood loss.

All that remains now is the steering wheel, a propeller, and the anchor.

In the movie’s original ending, the shark anticlimactically dies from blood loss while circling Brody. Spielberg changed this to the famous explosion scene, but not everyone agreed with his decision.

Spielberg didn’t direct the infamous explosion scene.

Peter Benchley was kicked off the set after protesting the change to his novel. He later conceded that Spielberg had made the right decision.

Spielberg called Jaws “his Vietnam.”

Exhausted from shooting, he had already returned to Hollywood to work on post-production, leaving the filming to the secondary crew.

“Jaws was my Vietnam.

It was basically naïve people against nature, and nature beat us every day.”