Everyone has heard rumors of people getting rid of unwanted items by tossing them into any kind of body of water. Whether it be junk that they don't want, or perhaps something more valuable instead.

There are many rumors and legends that speak of all sorts of things hidden beneath the surface, such as money, treasure, cities, or even aliens, believe it or not! People just don't know if the myths are true.

Some people believe we've explored the whole planet. That's just ignorant. 65% of the planet is covered by deep blue water.

This means that 65% of the world is undiscovered underneath. Scientists know a whole lot more about space than about what lies in the oceans. With humans being curious by nature, many people have wanted to debunk or to prove theories surrounding what lies beneath the surface of our oceans.

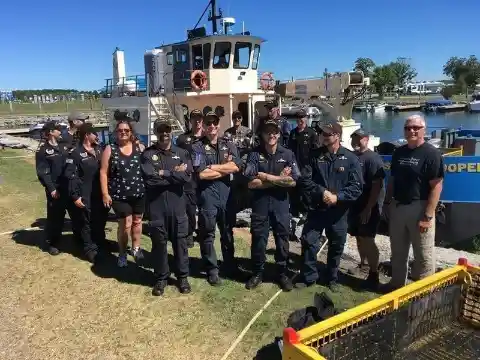

A scientific expedition to explore Lake Ontario in Canada was launched in August 2017. According to popular rumors, there's a lot of history at the bottom of the lake. The team hopes to find something special.

If they succeed in their mission it would change everything. They codenamed the expedition Raise The Arrow.

The team was working for a salvage company called OEX Recovery Group Inc. Their expertise lies in recovering salvage that's "in distress". They work together with financial and mining companies in Canada to help them find the salvage.

The company heard rumors of mysterious treasure sitting on the floor of the lake. This made them keen to get started.

Raise The Arrow was created for a singular purpose: to take the tales of valuable, remarkable treasure and act on them, recovering the high-value items as soon as they can.

OEX stated that the find would surprise the world and would definitely fund the project going forward.

The plan seemed simple, they had to look in areas with a good likelihood of finding these items. But even with a simple plan, they would be against the odds in finding any treasure. Whatever they find may be too heavy to lift off the floor or they might pass over the objects altogether if they're well hidden.

And the other possibility was that there was no truth to these rumors at all. Would it be worth it to fund an expensive expedition into the unknown with unlikely odds?

The surface surrounding the boat was still and quiet. Nothing was stirring the water. It was like the lake was waiting in anticipation for the crew to start their long-awaited expedition.

The team looked at the water together, trying to see into its depths. They couldn't see anything but that didn't dishearten them in their hunt. They all imagined what things could lie deep down in the lake.

The team had to keep their mouths shut. Since the rumors alluded to valuable treasure, they couldn't risk anyone else finding out about what they had their eyes set on. In the case that it wasn't any more than legend, the team didn't want to get their hopes up for anything.

They didn't even know what to look for. But this drove the passionate explorers even more.

There were reports of people seeing something in the water that disappeared as soon as they had laid eyes on it. The people who reported them were from a long time ago though, back in 1950.

60 years had passed since these reports had been made. One question still hung in their minds: what was it that all those people had seen?

The only relevant information about the reports was that the people had only seen the object for a brief moment and that there wasn't any time to figure out what they had seen. But there was one thing in common, the witnesses could never shake the experience from their mind.

For many years, the story would be told and wondered about. Until today, when the expedition decided to go into the water.

Finally, there was a chance for answers. The team of Raise The Arrow was hoping to answer the question once and for all.

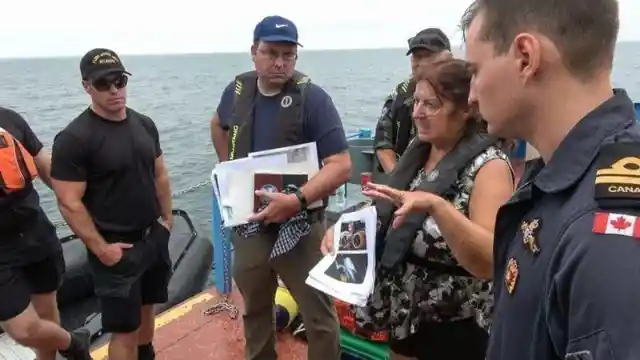

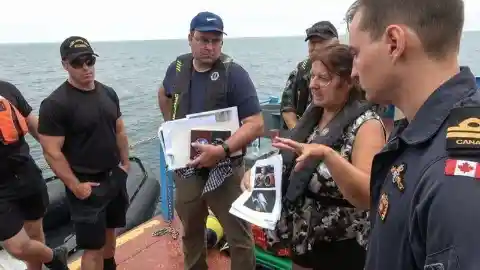

The locals eagerly shared the stories with the team. The one thing, however, that they couldn’t answers was what it might be.

The various witnesses happily pointed out where it happened. After leading them to the edge of the lake, a large area was pointed out offshore where the incident was supposed to have happened.

This gave the team a starting point at least. With all their gear ready, the team started to prepare for the adventure.

The area pointed out was called Point Petre, located on the northeastern shores of Lake Ontario. This little peninsula is in Ontario’s Prince Edward County.

There are no nearby urban areas as it is a protected wildlife conservation area.

The pebble beaches in the area are popular among tourists, as are the rock cliffs and limestone formations.

Like any other lake, legends accumulate around such areas. These contain all kinds of monsters and characters.

A famous example is Loch Ness in Scotland where the famous Loch Ness Monster, or Nessie, is rumored to live. Many scientists have labeled Nessie as a hoax but the high number of sightings make people wonder if it might be true.

Lake Ontario has been at the center of many rumors. In 2013 it was rumored that an alien species had created a base under the water of the lake.

Many people found the idea of aliens at the bottom of the lake exciting, despite the fact that it is unlikely.

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America, with shores in both Canada and the US. Its name means ‘Lake Of Shining Waters’ in the Huron language. It’s the smallest of the Great Lakes, although still the 13th largest lake in the world.

At the end of the Great Lake chain, Lake Ontario is the lowest at 243 feet (ca. 74 m) above sea level.

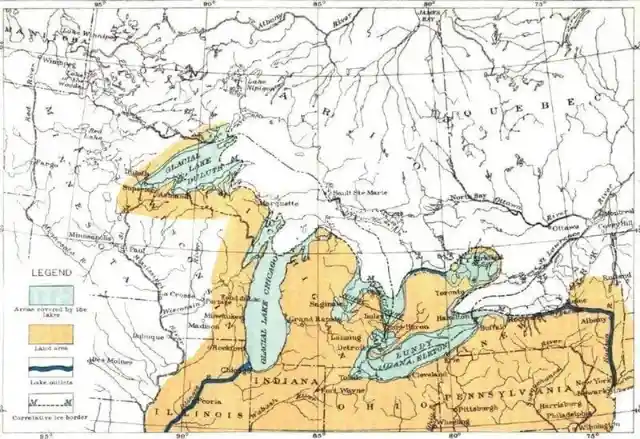

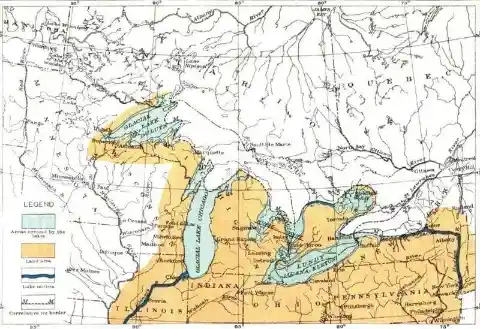

The lake was carved out by the Wisconsin ice sheet during the last ice age. At one point the lake was actually a bay on the Atlantic ocean. You can see dry beaches and banks up to 25 miles (ca.

40 km) from the current shores, tracing the changes to the lake over the millennia. With the weight of the glaciers gone, the plates floating on the lava inside the globe are still bouncing back upwards. As the land rises out of the water, it tips a little, and inhabitants of the southern shores lose a bit of their land to the hungry ripples.

634 miles (ca. 1,020 km) of shoreline surround the waters of the lake. A further 78 miles (ca. 126 km) outline its many islands.

At its deepest, it’s 133 fathoms to the bottom. Due to its depth, it never completely freezes in winter. The lake is fed by 10 rivers, including the Niagara river, waters tumbling down from the famous waterfalls to the southeast. Those waters leave by the St Lawrence River, stretching northeast on its way to the Atlantic ocean.

Cities border the shores of Lake Ontario, most notably Toronto on the Canadian side, and Rochester on the US side. But much of the lake is home to large wetlands, which support a varied ensemble of plant and animal species.

Pollution and deforestation have depleted many of the species native to the area. Nowadays the wetlands and forests surrounding the lake are protected areas.

Lake Ontario’s shores are thousands of years old. They contain nearly 400 cubic miles of dark, secretive water. They stretch across the border of two great nations. The task before the team was of Biblical proportions. But they had help.

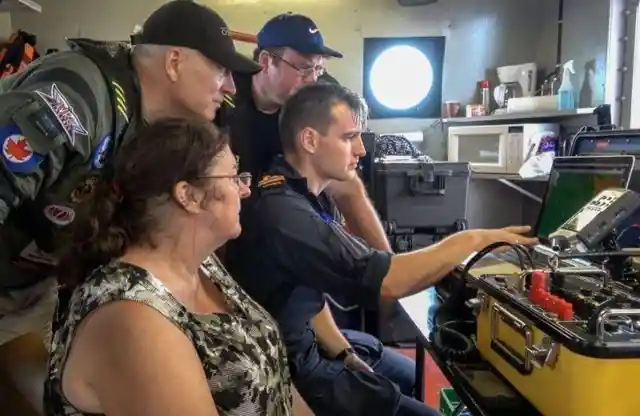

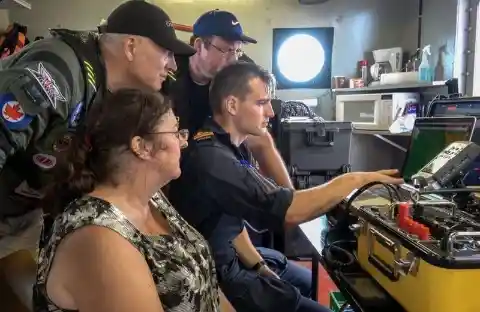

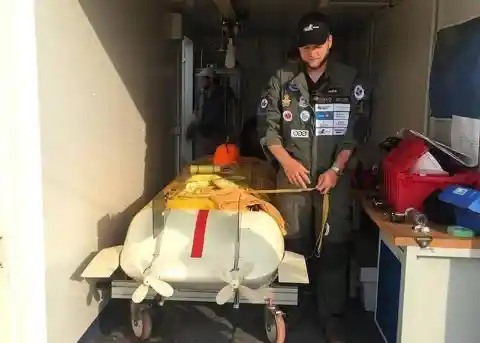

Meet the ThunderFish! This cute little craft is an automatic underwater vehicle, a mini-submarine. It’s pretty much a drone that swims instead of flies. Its camera is a sonar device that can take high-resolution images of the environment surrounding it.

No-one is living in this yellow submarine, though. The team remained on dry land whilst piloting it around the designated area of the lake bed. And the ThunderFish delivered. It sent wonderful images back to its gloating masters.

What did it see? All stories were put to the side now. There would be no made-up monsters, no alien invasions. They didn’t know what they were looking for, but there could be no doubt that the sonar images in front of them showed something.

What was it appearing on the screens before them? What could the nifty little probe be looking at, fathoms below them? The team craned forward over the images, trying to make some sense from them. As if they were squinting just right at a 3D picture, suddenly the shapes fell into place for the team.

It was an aircraft! But it wasn’t just any old aircraft. This one was special.

How special? I hear you ask. Well, let’s do a bit of time traveling, and see if we can spot the aircraft new and shiny, and not yet wet. Let’s peer in the windows of a hangar, somewhere in Canada, owned by the government, in 1946.

The second World War had just ended, but tensions between the Eastern and Western Blocs were high. Each side was looking for an edge over the other. The Canadian government was pinning its hopes on a new jet fighter with serious destructive capabilities.

The Cold War was beginning. Both sides were eager to gain a military advantage over the other in the event of a large-scale battle. The war ended in 1991 without such an encounter ever happening, thus earning its title, the ‘Cold’ War. For over 40 years the threat of invasion hung over the world.

On one side, the Western Bloc, generally democratic, headed by the US. On the other, the Eastern Bloc, communist, headed by the USSR. The emerging third world countries tried desperately to stay neutral.

Both East and West possessed the power to annihilate vast areas of land with one atomic bomb. No-one really wanted this to happen, and it was the threat from both sides that kept the other from attacking.

Nevertheless, the only way to feel safe is to have superior firepower. The Soviets started building aircraft that could carry their weapons over the Arctic to the US and Canada.

Canada saw the Soviet activity and raised it one Canadian company; A. V. Roe Canada Limited. Now known as Avro Canada, these were the engineers assigned to creating aircraft that could beat back the Russian threat.

And they delivered. In 1953, the Avro CF-100 Canuck was born. It was christened the Clunk and it remained on active service in the Canadian military until the 1980s.

In 1952, as they were developing old Clunk, the Royal Canadian Air Force received new intelligence. The Russians were upping the stakes once more. They were developing another aircraft. It was rumored to be a high-tech, high-speed, high-destruction animal that could wipe out the Canadian nation.

But it would take the Soviets seven years to perfect it. Canada had time. She put it to good use.

In 1953 the Clunk set out on her launch flight. Whilst people of note were saluting her, shadowy heads were already down, studying blueprints for her successor. The RCAF had already formulated a report in 1952, detailing how they could improve the Canuck. It was called ‘RCAF’s Final Report of the All-Weather Interceptor Requirements Team’.

All-weather interceptor didn’t exactly roll off the tongue, though, so A. V. Roe Canada called it the Avro Arrow.

She was everything that the name invoked. The Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow was a supersonic interceptor. With its delta wings, it looked like a spearhead, and it flew as one, true and deadly. The main specification improvements were in strength and speed. This baby could reach heights above 50,000 feet (ca.

15 km). She could fly at Mach 2 speeds. Mach 2 sounds pretty impressive, and when you think that it’s equal to 1500mph (ca. 2,414 km/h) you can see why!

Now back in the day, there were no computer simulation models to test theories with. No, engineers in those days had to make model prototypes. Before testing with these prototypes, it was impossible to know whether the theories would hold together in the air.

Between 1953 and 1957, nine prototypes of the Avro Arrow were constructed. They were perfect imitations of the hoped-for real thing, except that they were made to a smaller scale.

The Arrow was named for its distinctive delta wing design. Today, of course, we have seen delta wings on many aircraft, large and small. But back then, it was an innovative new concept. And it did a special job.

The barrier that aircraft engineers had long struggled to overcome was that of sound. The secret turned out to be in the wing shape. Delta wings create wave drag, which creates an awful lot of complicated vortexes and forces that enable the plane to fly faster than the speed of sound.

The nine Avro Arrow prototypes were each around 10 feet (ca. 3 m) long. Their wingspan was around 6.5 feet (ca. 2 m).

They weren’t quite carbon copies of their big sister, though. These mini-arrows ran on solid fuel. They were mounted on rocket boosters in order to reach the speed needed to test the wings for drag and stability issues. Then they were launched, from Point Petre, Lake Ontario.

These cute little aircraft turned out to really pack a punch. They reached Mach 1.7 before the glassy waters of lake claimed their prize. The engineers had the information that they needed to move the design to the next stage. Surprisingly little needed to be tweaked, based on the prototypes’ flight data.

The wings were drooped and given a camber. A dog-tooth was introduced. The newly-published area rule principle was applied, leading to changes such as a sharper nose and the addition of a tail cone.

The Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow was rolled out in October 1957. The plane bore the mark RL-201. It was to be a grand occasion, marking a turnaround in Canadian defenses. 13,000 guests were invited to the prestigious occasion.

But the Soviet Union, not to be outdone, defeated the Arrow before it even got off the ground. They launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial Earth satellite. This was far more exciting than a mere plane!

The Arrow was a well-designed aircraft, innovative and daring. It pushed the boundaries of flight as we then knew it. But, it was in the wrong place at the wrong time. With one move, the USSR had changed the Western world’s priorities.

Political change heralded the demise of the Arrow. The government changed hands and new treaties were signed with the US. Most importantly, the arrival of Sputnik on the scene meant that there was now a threat from even higher up.

The country could not afford defensive systems against both manned bombers and possible ballistic attacks from space. Canada would have to make a choice. The Arrows went down fighting, with various government and military officials reluctant to cancel the scheme.

But in the end, ballistic missiles were deemed to be the greater threat. Canada installed the Bomarc system and the Arrow program was canceled in 1959.

The cancellation of the program resulted in nearly 50,000 people put out of work. All the planes, their parts, equipment, and data were destroyed. The Canadian Mounted Police suspected a Soviet mole in A.

V. Coe Canada and wanted all evidence disposed of. But they had forgotten about the nine prototypes buried in the bed of Lake Ontario.

“The government destroyed all the drawings, models and burned everything so it wasn’t replicated,” David Shea, senior engineer, told the National Post.

“These models, at the bottom of Lake Ontario, are the only intact pieces of that whole program.” David works for Kraken Sonar, one of the companies that provide equipment for the project known as Raise The Arrow, organized by OEX Recovery Group Incorporated.

It was Kraken Sonar who gave the team their ThunderFish. It was this submarine drone that took the first fateful pictures of the prototypes. “Back in the 1950s, there was no computer modeling to see how they’d fly, so the designers had to use a physical model,” Karl Kenny, also from Kraken Sonar, added.

“Then, it went back to the engineers for fine-tuning. The ninth model is the Holy Grail. They had it perfected.”

John Burzynski is the president, CEO, and director of Osisko Mining, another company involved with the Raise The Arrow project. He is excited about the prospect of bringing these unique aircraft back to the surface.

“As professional explorers in the mining business, we initiated this program about a year ago with the idea of bringing back a piece of lost Canadian history to the Canadian public,” he confirmed in the same interview.

The area off of the shores of Point Petre seemed like a sensible place to start.

After all, that’s where the prototypes were launched all those years ago.

Jack Hurst is one of the few remaining witnesses prepared to help find the elusive aircraft. He was there, over six decades ago, when they were launched. He saw the object that was there and then gone.

“I would guess that [the models] went a few thousand feet in the air and I don’t think they would be much more than a mile out,” he declared. It was his direction that decided where the Raise The Arrow team would start looking.

According to Burzynski, the team was confident that they would find something very early in their search. “We’re starting with the high-probability areas,” he told CBC TV. They had done their research well.

“You won’t have to wait weeks and months. This will be within days,” he insisted. The media was stunned at how fast they found what they were looking for.

Twelve short days later, Burzynski was back. “Well, we found one,” he exclaimed. It was late July when the team got their proof that the aircraft were indeed under the lake.

But the prototypes were destined to spend a few more months in their quiet resting place before they could be raised. The world could not get their first glimpse of the amazing artifacts until 2018.

History was nonetheless coming to life in front of us. The prospect of raising the Arrows was super exciting.

David Shea was as enthusiastic about the discovery as his colleague, Burzynski. “I think being able to showcase using cutting-edge Canadian technology — being our sonar systems and underwater vehicles — to actually find and resurrect cutting edge Canadian technology… I think it’s an amazing example of what we can do as Canadians looking back at our history.”

The delay in bringing the prototypes back to light was a big one. The team hadn’t found all nine of the aircraft. Of course, they were determined to get the whole set. The prototype that was missing was the ninth to be made.

It was the most advanced, the most like the eventual aircraft proper would be. It had to be there. The team just needed more time.

It hadn’t taken long to find the first eight prototypes. This was huge news. The aircraft are a part of Canadian history.

Only 6 of the finished craft were made, and all destroyed. Being able to see the trailblazing aircraft would be amazing. “The delta wing was a relatively new concept at that point, so it required a lot of testing to determine whether it would perform well, particularly at supersonic speeds,” said Erin Gregory from the Canada Aviation & Space Museum.

After a year of excitement, disbelief, struggle, and plain hard work, the team celebrated at last. “We are pleased to announce that the first historic relic of the Avro Arrow free-flight program has been recovered,” their Facebook page proclaimed.

“It was delivered back to land at CFB Trenton on August 13, 2018, after resting on the bed of Lake Ontario for over 64 years.”

Osisko Mining, Kraken Sonar, OEX Recovery Group Incorporated, and the Canadian public are still hoping to find the last prototype. Burzynski, Shea, Kenny and co are sure that they can do it.

The ninth plane is still eluding capture, but the team is dogged in their determination to bring it to light. The Raise The Arrow project is due to continue until it can be found.