Why The Past Is So Cool

The most interesting thing about the past is that it remains unknown until at least one person finds out about it. The past can only be discovered through its traces that have remained in the world until the present time.

But these traces can sometimes be almost impossible to find and once you've found them, you must be able to interpret it, which is hard in itself. Finding out exactly what something tells us about the past is hard. This was the case when something was found in the mountains of Tibet.

Qyalwa

Qyalwa was a shepard in Quesang in 1982. Quesang was a region on the Tibetan Plateau where he would hike in the mountains while watching over his goats.

It was easy for him. He loved nature and the peace that came with it. It was quiet and he loved the silence. But on this very day, it was different.

Gone With The Wind

It was absolutely necessary for Gyalwa to bring his great shepherd dog with him to take care of the cattle. The dog would kept the goats in line, and served as Gyalwa's companion in the mountains.

But one day, while Gyalwa was taking his usual nap, something happened. The great shepherd dog disappeared.

Waking Up

Gyalwa woke up from the sounds that the goats were making. He looked around as he rubbed the sleep from his eyes, trying his best to make sure everything was all right in his sleepy state. But that's when he realized that the dog was gone.

He was alarmed! He quickly got up and started searching for it in the rocky hills.

Can't Find The Dog

H couldn't afford to lose it. The dog helped him greatly with the goats and he couldn't afford to get a new one. The dog was also his friend, he couldn't lose a friend.

He couldn't find it anywhere.

Swallow His Fears

He didn't give up. He was still desperately searching when he discovered a save in the mountain. It was deep and dark. He had no idea what could be waiting inside of it, he was scared to enter it. But he had to find the dog. If it had gotten hurt in the cave, and he didn't help it, he would never be able to forgive himself.

Gyalwa decided to swallow his fears and enter the cave.

Going In

He was overjoyed to see the dog inside. He ran up to it excitedly, only to discover that it was scared and moaning as it leaned against the cave's cold walls.

But then, Gyalwa saw something that he never expected to see.

Rumors And Legends

He noticed imprints of hands and feet on one of the cave's walls. It appeared to be made by a small child, or possibly a small creature which closely resembled a human. It was a bit creepy.

He quickly picked up his dog and ran out of the cave, spooked by what he saw. He told the villagers about it the next day. After that, plenty of rumors and legends began to circulate around the region about the origin of what he had found. But the truth was only revealed 30 years after the discovery.

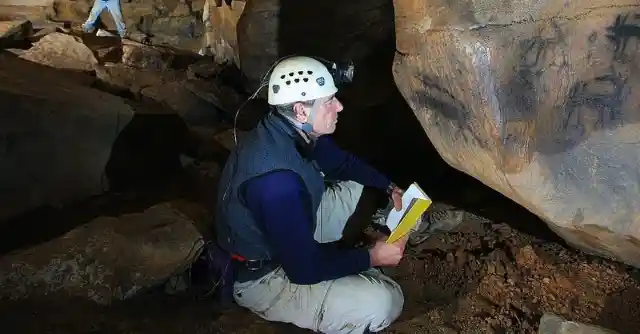

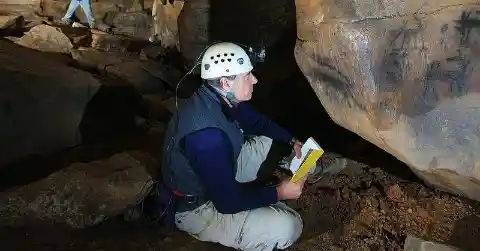

Archeologist's Research

In 2018, the imprints were analyzed by the academic community. David Zhang was a Chinese archeologist and he had heard all of the rumors and legends surrounding the imprints of Quesang. He wanted to know what the truth about these imprints were, so he decided to investigate them by his own means.

What he found was one of the most important findings about our past as a species.

Oldest Cave Art Ever

It was the work of a prehistoric human. But these imprints had a surprising detail.

What was this detail? Their dating. They were over 200,000 years old. They are the oldest piece of parietal or cave art that has ever been discovered by humans. The oldest known cave painting is only about 64,000 years old, to put things into perspective.

The Authors Of The Imprints

This was not the only surprising thing about the imprints in Quesang. After studying them, Zhang concluded that they were made by two children: one of the age of 7, the other of the age of 12.

If that were true, not only would we be talking about the oldest piece of cave art ever, but also about the first one ever found that was the work of children. However, how did they do the imprints?

How Were They Made?

The answer is simple: at the beginning, the surface in which the hands were imprinted was mud. But after millenia, the mud had solidified (lithified is the technical term) into travertine, a type of rock.

But still, one question remained about this primigene work of art.

Are They Really Art?

Were the imprints the result of deliberate and intentional action? In other words: did the children who imprinted their hands in the mud actually intend to create an image on its surface?

If and only if the answer to that question is positive can we be sure that the imprints of Quesang are a work of parietal art? If they were not created for the sake of its visual aspect, but just the result of playing with or touching the mud with no further intention, then it’s unjustified to call them a work of art.

Academic Controversy

Different scholars are divided about this question. Zhang, of course, has tried to make his discovery as big as possible: it is quite a merit to have discovered the most ancient piece of art in the world.

Others are more skeptical. For instance, Pablo Mayoral, a Spanish paleontologist, declared: “I find it difficult to think that there is an ‘intentionality’ in this design. And I don’t think there are scientific criteria to prove it—it is a question of faith, and of wanting to see things in one way or another.”

The Mysteries Of History

Maybe we’ll never know. As was said at the beginning of this article, the past is something that can only be known indirectly; there are some things about it that we will never be able to know.

But isn’t it appealing to think that the drive for art and the search for beauty has always been present in the spirit of humanity, even within those Tibetan children from 200,000 years ago?